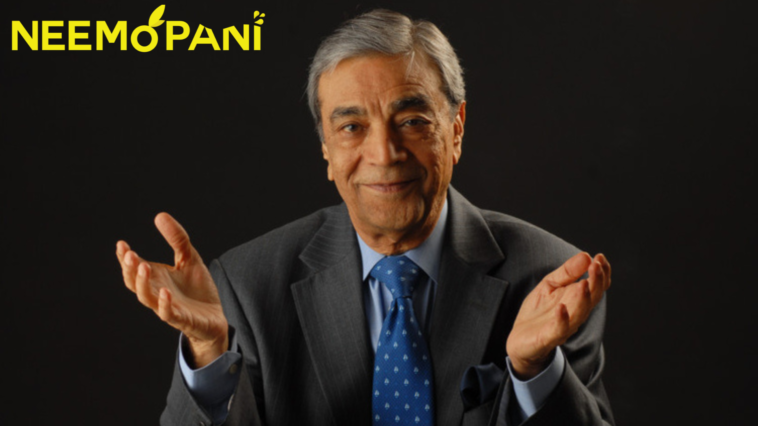

Remembering the various roles that Mohyeddin played during his lifetime was the focus of the second day of the Zia Mohyeddin Festival at the National Academy of Performing Arts in Napa. There were sobs, cheers, laughing, and moments of stillness, but the most noticeable thing was a palpable sense of loss that pervaded the entire room.

An expressive father:

Zia’s firstborn, Risha Mohyeddin, resembles his late father in every way. Risha, a banker by trade, reflected on his early memories and recalled Zia as someone who stayed to himself at all times.

“He wasn’t very expressive. He always tried to keep his emotions to himself. People often comment on his attention to detail and his perfectionism, but what they don’t often talk about is how difficult it is to live with a perfectionist,” he paused. “I give credit to Azra for mellowing him out. But I remember I always found it interesting how he had an issue with why other people around him weren’t perfectionists like him. He’d actually get upset over why people are okay with mediocrity and average work,” he laughed.

Aliya Mohyeddin, Zia’s last born with his third wife Azra Mohyeddin, was not just Zia’s only daughter but also his only child that ever got to work in a production directed by the late legend. “One day when he was working on Waiting for Godot, he came home and walked to me and said, ‘I’m looking for a boy,’ and that’s all he said. I said okay, that’s cool, not knowing what he really meant. After a few days, he came to me again and said, ‘You’ll be my boy’ and I was quite surprised but I later learnt that the character in the production was literally called ‘boy,’” she smiled.

Not a demanding husband:

Azra shared little moments from the time she spent with Zia to cherish how good of a husband he was to her. “I’d attend his dramas and plays but when I couldn’t, I always asked him how they went. If he said it was fine, then it meant it was amazing. Anyway, I wasn’t there for a few dramas in a row and he came to me and said, ‘Joonum, ap mujhe kuch samjhti hee nahi hain (You don’t think anything of me)” and I laughed. He knew what he meant to me,” she said.

Another story she had was about how he’d always take a step back when stepping outside the house, getting in the car, and entering a hall to make space for her to walk ahead. “His sisters would complain that he doesn’t stop me from doing certain things and he’d come to me and say, ‘Hamsheera was telling me to stop you from something or say something. What am I supposed to do exactly, I don’t understand.’ He never stopped me. We never had arguments about silly patriarchal subjects that our society sees examples of every day. Others have complaints and I am not saying that they aren’t true but I’d just say that when he came into my life, he was a great husband.”

1677227259-0/mobile_file_2023-02-24_08-25-36-(1)1677227259-0.jpg)

A true gentleman:

Zehra Nigah, a poet who was close to Mohyeddin, especially while he was filming in London, wanted to shed light on how he was the epitome of mannerism and discipline. “Apart from the fact that he was a great artist, he was a complete gentleman, the most cultured one can be, which is impossible to find in this time, sorry to say. There was no room for you to point out any mistake in his demeanour. From how to walk, stand, eat, and even say goodbye, he was perfect. We would wait for him and notice his actions to point out one thing that he did wrong or inappropriately but no. Never,” her voice echoed.

“He used to speak such English in a way that even the English-speaking world would be amazed. Similarly, with Urdu, his voice would make you feel like he’s painting a scenery where flowers are blooming and leaves are falling. His Persian would sound like poetry to the ears. I never had the chance to hear him speak Punjabi but he used to talk to Faiz Ahmed Faiz in Punjabi a lot.”

The poet emphasised that if there was one thing that Mohyeddin couldn’t tolerate, it was the disrespect of language.

A foodie:

Anybody who spent time with Zia was aware of how difficult it was to satisfy his palate. Zia was never a simple “daal roti salan,” according to his wife Azra, who also took sure to keep dinners formal. Zia preferred lavish feasts. She recounted, “One time I even recorded how he’d enjoy 5–6 dishes on the dinner table, all prepared in a lovely fashion, but he’d take only a nibble from each.”

Everyone on the panel had a story to share about a food-related incident. His nephew laughed as he related how he once called the chef and complimented him on his “gift” for being able to make cuisine that is so terrible on its own.

Risha, his son, also shared how they were guests at someone’s place in Birmingham and at the dinner table, Zia said, “‘Wow! I’ve never had such kebabs before.’ but when we got in the car, he complained about how terrible the kebabs were. When I confronted him on how he said something else in their house, he said, ‘I didn’t lie. I’ve never had such bad kebabs ever in my life.’”

A winner at life:

Munawwar Siddiqui, who has known Zia sahab for over 60 years, and has worked with him in theatre, film and TV, shared how Zia convinced Khwaja Moinuddin to make the first drama with an actual set instead of a screen with drawings on it. “We were working on Lal Qile se Lalukhet Tak and he walked up to Khawaja sahab and said I want to direct your play and I want to do it with a full set and that was a bizarre thing to say at that time because we never shot with sets but Zia made it happen. At that time, we spent months together.”

Munawwar Siddiqui, who has known Zia sahab for over 60 years, and has worked with him in theatre, film and TV, shared how Zia convinced Khwaja Moinuddin to make the first drama with an actual set instead of a screen with drawings on it. “We were working on Lal Qile se Lalukhet Tak and he walked up to Khawaja sahab and said I want to direct your play and I want to do it with a full set and that was a bizarre thing to say at that time because we never shot with sets but Zia made it happen. At that time, we spent months together.”