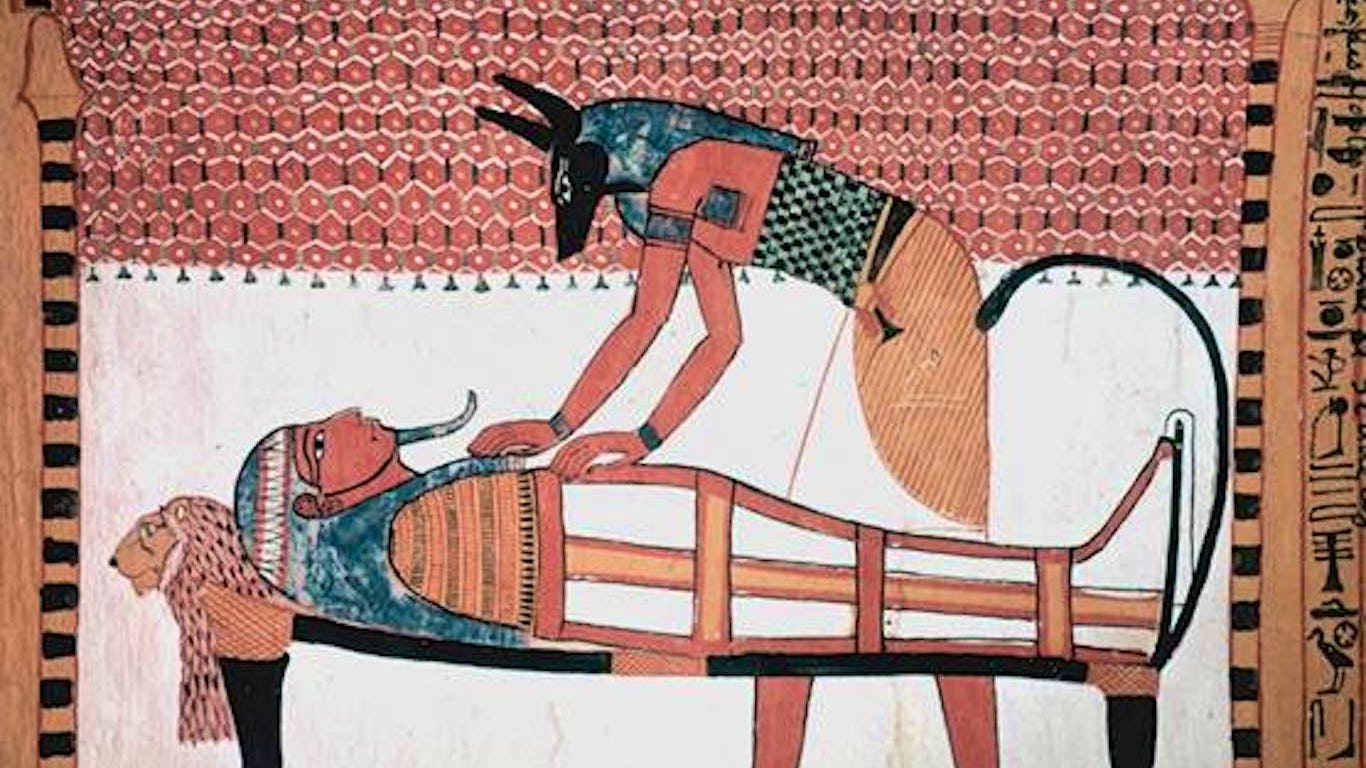

Thanks to the discovery of dozens of beakers and bowls in a mummification workshop, it has been revealed how ancient Egyptians embalmed their dead, using some “surprising” ingredients imported from as far away as Southeast Asia.

The extraordinary pottery collection, which dates to roughly 664-525 BC, was discovered in 2016 at the bottom of a well that was 13 metres (42 feet) deep at the Saqqara Necropolis south of Cairo.

Researchers found bitumen from the Dead Sea, cedar oil from Lebanon, and tree resin from Asia inside the vessels, demonstrating how global trade helped embalmers find the best components available worldwide. Since they thought that if bodies were preserved, they would make it to the afterlife, the ancient Egyptians devised an astoundingly sophisticated method of embalming corpses.

But exactly how this was done has largely remained lost to time.

A team of researchers from Germany’s Tuebingen and Munich universities in collaboration with the National Research Centre in Cairo has found some answers by analysing the residue in 31 ceramic vessels found at the Saqqara mummification workshop.

The substances had “antifungal, anti-bacterial properties” which helped “preserve human tissues and reduce unpleasant smells,” the study’s lead author, Maxime Rageot, told a press conference.

One of the most surprising findings was the presence of resins, such as dammar and elemi, which likely came from tropical forests in Southeast Asia, as well as signs of Pistacia, juniper, cypress and olive trees from the Mediterranean.

The diversity of substances shows that the industry of embalming drove momentum for globalisation. The embalmers are believed to have taken advantage of a trade route that came to Egypt through present-day Indonesia, India, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea from around 2000 BC.

The mummification process took up to 70 days involving desiccating the body with natron salt, and evisceration to remove the lungs, stomach, intestines and liver.